Border / Security / Witness

what one deems existential, and what one attaches indispensability to and deems worthy of any and all protection, is made up

Some time ago, I rewatched the new Hunger Games prequel, and then read this review of the first book by Rob Horning, where he identifies the book’s premise (dystopian, televised children-on-children battles as an effective tool of tyrannical control) as being believable due to its “potentiality of vicariousness, which our own experience confirms, makes this system of control possible.” What will we do, what will we let someone get away with, if the prize is witness? Horning describes Katniss’ emotionality as devoid of contextual reference points, her story as something she cannot consume (or indeed, live) herself, only perform. In what I found a striking description of the tussle between survival and some rudimentary attempt at ‘authenticity’ (or reality), Horning writes of Katniss:

It's not clear even to her in the end whether her emotional reactions are real or strategic performances. The economic pressures of the moment make them feel real then and dubious afterward.

This strikes me as not so differentiated from Michelle Santiago Cortés’ diagnosis of the mediation of the online world in people’s ability to exist, or rather, their inability to exist without being perceived: “People are still posting, liking, sharing; trying to find and become themselves with every click.” Not dissimilarly, what hit me most (and most immediately) about Horning’s analysis was the use of the term “economic pressures” to describe having to choose between living and being killed. Used as a metaphor, it is quite intuitive — this choice involves a calculus, a weighing up: seemingly ‘economic’ considerations and mechanisms funneled towards a non-economic subject — life.

However, used more literally, I think it's perhaps even more accurate: materialism is, at this stage, a near-tired trope of analysis (in some circles), but when the choice of life and death is placed within the specific world it inhabits, beyond the arena, the economics of it become realized in more ways than one: Katniss is a commodity here, making her own (constrained) decisions about how she may be commodified; she is a fundamentally economic resource to her loved ones and to herself, and she must choose how best to utilize, fetishize, represent, and spectacularize herself.

“The arena is everywhere,” according to Viola Davis’ Dr. Gaul in the prequel, the actual game and its rules just saying the quiet part out loud about how we live and how we treat each other — what we are willing to do in service of our needs, what we are willing to define as needs, what we are willing to let ourselves get away with, what moralities or hesitations we are willing to suspend if enough people want to watch us do so.

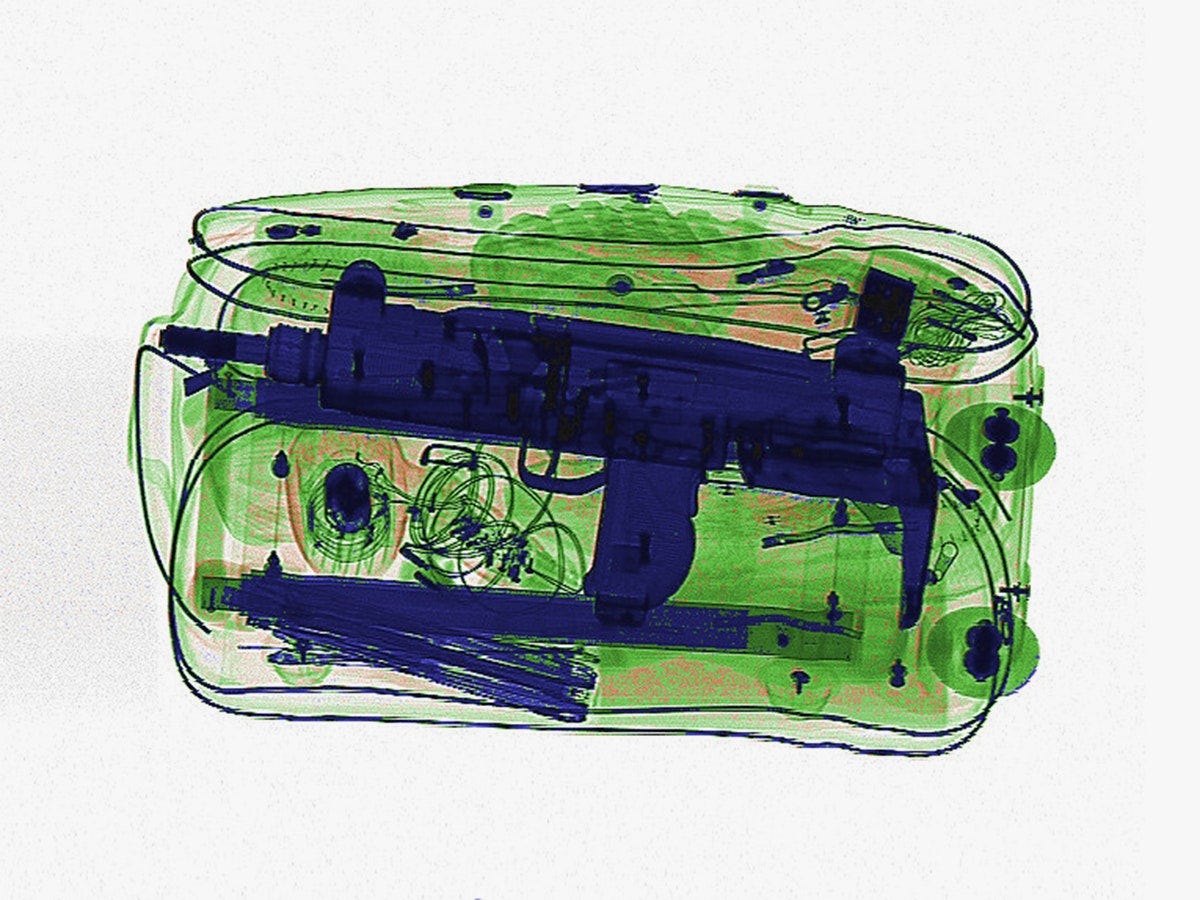

Around the same time as Horning’s review, I read this interview of Harsha Walia by Ayesha A. Siddiqi, where the first question names the concept of ‘securitization’: the process of making the previously unthinkable permissible, suspending ‘the norm’ to allow for what would normally be called an ‘excess’ of power, by pointing to a threat that is constructed as inarguably existential. This isn’t done overnight, of course, and the garnering (or sidelining) of permission occurs only following a systematic process of persuasion, where an ‘audience’ becomes convinced that yes, it is reasonable, or even necessary, or even good that we need to take our shoes off at airports now, that children are put in cages and taken from their families at international borders, that launching ‘global’ military campaigns is an excellent idea.

Of course, what one deems existential, and what one attaches indispensability to and deems worthy of any and all protection, is made up, if not entirely, then to a great extent, of what one already thinks, believes, and wants. Walia says:

In Canada, the Immigration and Refugee Board is starting to pilot algorithmic AI decision-making to decide if someone is a refugee or not, and whether they'll get to stay or be deported. … This massive industry is a dystopic testing ground that is used against not only against migrants and refugees but they certainly are one of the many populations against whom it’s weaponized.

When I think about this — about borders, surveillance, capital, moral-aesthetic productions of bureaucratic, taxonomised, disparate violence — I feel pulled in too many different directions, overwhelmed and destabilized not just emotionally but analytically, intellectually. Walia describes citizenship as an “arbitrary privilege”, a fact she identifies as laid bare by the popularization of things like citizenship “investment programs”, stating that “it's not really true that people can't move. It's that people who represent capital absolutely can move in various forms, whether that's investor-based citizenship [or] high skilled visa programs, whether that’s tourism, whatever it is.”

In her essay Unlived Security, Akshi Singh places spatiality, and space itself, front and center in her analysis of the colonial, delineating a deep-rooted connection between it and the notion of ‘security’: “Security is the shared shibboleth that can’t be questioned, much like borders.” (Emphasis added.) Walia also alludes to this idea of security as an impenetrable claim: “We see the pandemic really exacerbating bordering regimes (which is to securitize borders and close the borders) but have it remain open to capitalist interest and to cheapened labor supply, and also open to deportation.” Crucially, and somewhat conversely, she identifies a porousness in the border (as entity, as concept, as object) itself: the subjectivity of its enforcement, noting capital itself as the primary dictator of commodity flow and of prioritization, forming a kind of overlapping super-object with the concept of security itself — a constituent, quiet component of the “shared shibboleth”.

This power-force of border maintenance and weaponization, I think, replicates and structurally collapses into (spatially) smaller and (in some ways) seemingly lower-stakes settings. Mary Gaitskill describes the use of the liberal impulse of “happiness” as an “expected norm” as a tool that exacerbates issues of “safety”:

That they are fixating on problems they can control and maybe solve (the pronouncement of offending words, gender madness, “shitty” men, “problematic” assigned reading material) is understandable. That they want the safety -- or the illusion of safety -- provided by the corrective apparatus is also understandable. Only a fool would not crave safety in the face what is happening now. But while the corrective apparatus is providing a measure of control, it cannot really provide safety.

It does this, I think, by mutating the idea of safety into a perverse, unquestionable call to “security” (while not always saying this word out loud), a thing that has been linguistically and rhetorically degraded to the point of being forbidden as an object of scrutiny. “Safety”, of course, is subjective, and this subjectivity (and the necessarily exclusionary, violent framing of it) are erased by invoking it as a tool for the upholding of victimhood.

What (or who) is threatened, endangered, subject to threat becomes immediately virtuous — whether it’s a nation’s white population or an individual suffering interpersonal harm. Walia:

There is this tendency towards thinking like, “I don't have a problem with racialized people, I just had a problem with illegals” right? But we see statistically that, for example, in the United States, the largest nationality of people who are technically “illegal” - who have overstayed their visas, are actually Canadians.

And Singh:

European man had a claim to land because he could understand its value—he could make it productive. The native couldn’t, and by this logic, the land was available for taking by those who could realize its potential.

Here, there is the revelation of a very standard, boring hypocrisy about where morality is situated, where it necessarily originates from, and how it is aesthetically represented: in an essentialised whiteness, with an undisplaceable quality of goodness, familiarity, and ‘safety’ projected, represented onto it — illegality a subjective quality reserved for non-white people (i.e. those who are deemed aesthetically repulsive), ‘value’ and ‘potential’ signaling intellect, and thereby a claim to objective superiority, which can then be seamlessly extrapolated to produce the logical end of murder.

David Lloyd, in his book Under Representation, describes the Subaltern as representing a “counterpossibilty”, referring to Ranajit Guha’s definition of the term as one that “does not represent any social positivity but appears as the negation of all other classes”. Lloyd points to Marx’s analysis of solidarity within the post-Revolutionary French peasantry, describing it as “predicated on the sheer contiguity of their existence” — that is, made up of coincidental proximity, rather than the identification of the commonality in their conditions or their desires as a class: “Unable to represent themselves, they look outside themselves to the state” (Lloyd).

‘Representation’, then, is a kind of spectacular realization of existence, a bureaucratised, intersubjectively verified projection of one’s pseudo-shared reality, made up of taxonomised, recognisable components that let the constituent individuals of a ‘community’ seek commune within it. Where Marx (and Lloyd) identified the state as the thing a contiguous, un-represented class looks to for an outward realization of their reality, I think it is now perhaps more useful to specifically identify the border — itself a representation of what the state is made of: control, surveillance, moral taxonomisation, and violence. The classical conception of a nation-state (population, territory, sovereignty, government), manifests more specifically as the ability to perpetuate existence via murder. As Walia points out, “We see border securitization happening inland too.” That is, the border is no longer just a location, but a fluctuating and mutable analytical and bureaucratic threshold, formed (and continually reproduced) in service of the super-object of capital and security, its permeability becoming theoretically absolute in its service.

Singh writes of her time in Scotland:

As my visa approached its expiration date, I decided to apply for settlement in the United Kingdom. Of course, it isn’t called anything as straightforward as settlement—it is called “Indefinite Leave to Remain” —and this term captures the profound ambivalence of this country towards its migrants. They allow, sometimes need, you to remain, but they’d rather you leave. Settlement was a form of security. I would keep my Indian passport, but I wouldn’t have to renew my visa every few years, or pay the yearly immigration health surcharge. I wouldn’t need to be in full-time employment or education to stay in the country. I spent my evenings studying for the mandatory “Life in the UK” test, learning to answer multiple choice questions about the Tudors and Stuarts, the Welsh, Scottish, and Northern Irish patron saints and parliaments, as well as British values, manners, and customs.

When I read this, I felt a kind of relief just from the description of something so tantalizing. I felt a vicarious ability to breathe. As I read more of Singh’s experience with the immigration bureaucracy, the medical bureaucracy, the academic bureaucracy in the UK, I tightened again, my exhalation feeling like a false-won respite from a nightmare that isn’t even my own. I tried this, I tried to apply for leave to remain, I had the luxury to leave and come home to a place where I am safe and healthy and financially ‘secure’. Singh’s account feeds into the changing locations of border violence, its endless exceptionalities and flexibilities to make room for (and in fact, resolve) its contradictions. How the term (and then, the concept of) ‘precarity’ functions as an aestheticised moderation of what truly can feel like existential, mind-numbing terror at the permanent instability of your home, your income, your life, let alone anything you wish to create or do with it. Discussing a similar precarity, Porpentine, in the essay Hot Allostatic Load, writes of the limitations it poses to one’s creativity: “Immaculate is boring and impossible. Health based aesthetic.”

While israel and its existence, its treatment of Palestine and Palestinians, is often viewed as an exception to the rule of ‘international order’, I think it is accurate to say that the events in Palestine (and Lebanon and Syria) stem from a very pervasive, universally realised logics of securitisation and aestheticization. Of the walls used by israel to insulate its people from the reality of genocide, Singh writes, “Proximity, history, responsibility—this is what the walls are in service of denying. This denial, we could argue, is the function of security.” The manufactured aesthetic cleanness of genocide is a function of border as division, as taxonomy, as representation: when the thing that represents a people (such as israel’s) is neat and tidy, covering anything unpleasant, the people themselves will believe this of themselves, attach their nationhood and their identity to that cleanness: the domain of aesthetic representation allows for a much more robust and impermeable model for self-identification, while ironically serving as a tool (in the literal, tangible sense) of hiding what is truly there, what it is helping create.

Of this impermeability, again: “In a series of responses to war in Gaza—collected in 2009—Jacqueline Rose quotes an Israeli human rights activist: “at the mention of the word security . . . everyone stands up straight and stops thinking.”” (Singh.) Is security, then, the commission of violence, or the erasure of it? The current stage of genocide in Gaza and Palestine more broadly represents a combination of the two: from scholasticide to the systemic, deliberate murdering of children, there is an effort not just to eradicate the Palestinian people but to destroy any trace of the process, any memory of its occurrence.

The targeting of journalists is not limited to israel’s wish to prevent the international community from knowing about what they’re doing — the IOF specifically and israelis more broadly have made it very clear they aren’t impacted by this one way or another, and international community is now made up of people who know the extent of the horrors and people who are pretending not to. The systemic attacks of journalists and chroniclers like Refaat Alareer is instead in service of a totalising, all-encompassing project of the erasure and dismantling of any record of what exists/ed and what occurred. It is a seismic collision of the pretense of righteousness that israel touts and the inevitable shame (and ‘accountability’, whatever form that may take) that will find it — its need to secure itself from the contradictions of what it is doing and what it pretends to believe it is doing.

Some time ago, I wrote that the modern conception of bureaucracy holds at its core the idea of verifiability, or the intersubjective agreement of something being ‘objectively’ true. This belief is produced through a combination of capitalistic control and coercion, with an ‘authority’ appropriating truth as concept by either (1) accessing enough influence/loyalty to create truth through ‘expertise’ or other force of accumulated capital, or (2) pointing to the process of recording (production/creation) and presenting it as undoctorable, necessarily accurate, objective, performing a removal of subjective agency, and achieving a shared belief in its impermeable or inarguable nature. This, importantly, locates the production of truth in the act of recording (or in fact, witnessing) it.

However, the most ‘well-documented’ genocide in history, israel’s actions in Palestine currently provoked little to no international response — israel enjoys the kind of commanding loyalty that lets it create alternative reality, where things as real as its own soldiers committing (and celebrating) horrific acts of violence and denigration against Palestinians, their bodies, and their homes somehow become questionable, up for debate, far from the effective monopoly on truth that videographic evidence carried (at least in popular culture) for decades.

Why? Again, from Unlived Security: “at the mention of the word security . . . everyone stands up straight and stops thinking.” Of course, this is the logical end of capitalism, a racialized system that fetishises hierarchical exploitation (named ‘profit’) above all else. Mark Fisher, on bureaucracy:

The way value is generated on the stock exchange depends of course less on what a company ‘really does’, and more on perceptions of, and beliefs about, its (future) performance. In capitalism, that is to say, all that is solid melts into PR, and late capitalism is defined at least as much by this ubiquitous tendency towards PR-production as it is by the imposition of market mechanisms.

Security, then, is this PR-production, and it is increasingly realized in the form of border violence(s) — the need for ‘security’ continues to translate into the need to be as big and strong as humanly possible, justifying expansionism, the world being viewed (or represented) as a complex of disparate, dislodged, decontextualised entities that live within their own systems and have the ‘right’ to perceive any (spatial or otherwise) externality as outside of its sphere of reality. This is an overwrought attempt to delineate the mechanisms of dehumanisation, an increasingly inadequate term constantly used to explain away how people can do the things they do, how people can think the things they do, live the way they do.

The border, in both a physical and imagined sense, is permeable, as Walia points out. ‘Security’, the ephemeral and intangible representative object, which manifests as the object of the border while hiding the reality of its concepts, is not. The “shibboleth that can’t be questioned”, it is increasingly indistinguishable from capital — a similarly unplaceable object of endless utility, readily available to justify the very worst of what is possible for a state, a system, a ‘community’, or its constituent individuals, to do.

Thank you for reading; this essay was a long-ish term project and I’m eager to spend more time working on similar, more research-intensive pieces that will hopefully produce work that is both valuable and informative. In future, the majority of posts such as this will be paywalled; this is public in hope of giving readers an idea of what to expect.