Assemblage: Hindsight

Arpita Singh + Videodrome (1983) + miscellany | YAMUNA RIVER | THE CUSTARD APPLE SUN | ← YOU ARE HERE

Once again a short little letter of what I’m putting into my brain, and my thoughts, where doable, about whether you should put it into yours. Here are also some photos of beautiful trees.

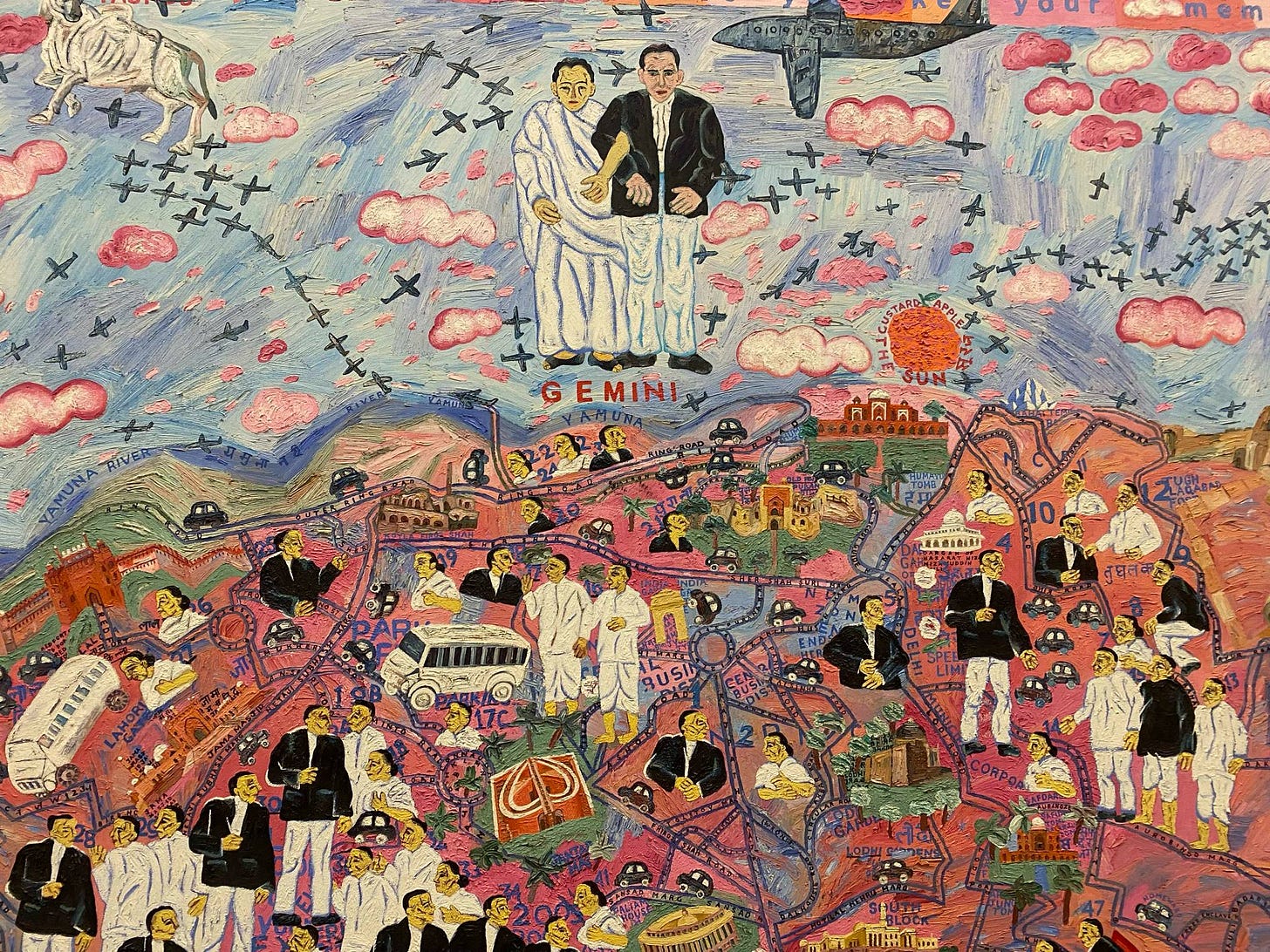

Arpita Singh: Remembering

This is a bit delayed, and I’d originally planned a longer-form piece on this exhibition, following what I wrote about the Tate. But I was becoming increasingly eager to talk about it, so here. I saw Remembering, Singh’s first solo exhibition outside India, at the Serpentine North in London in April of this year. I was genuinely overwhelmed by the sheer, intense beauty of it.

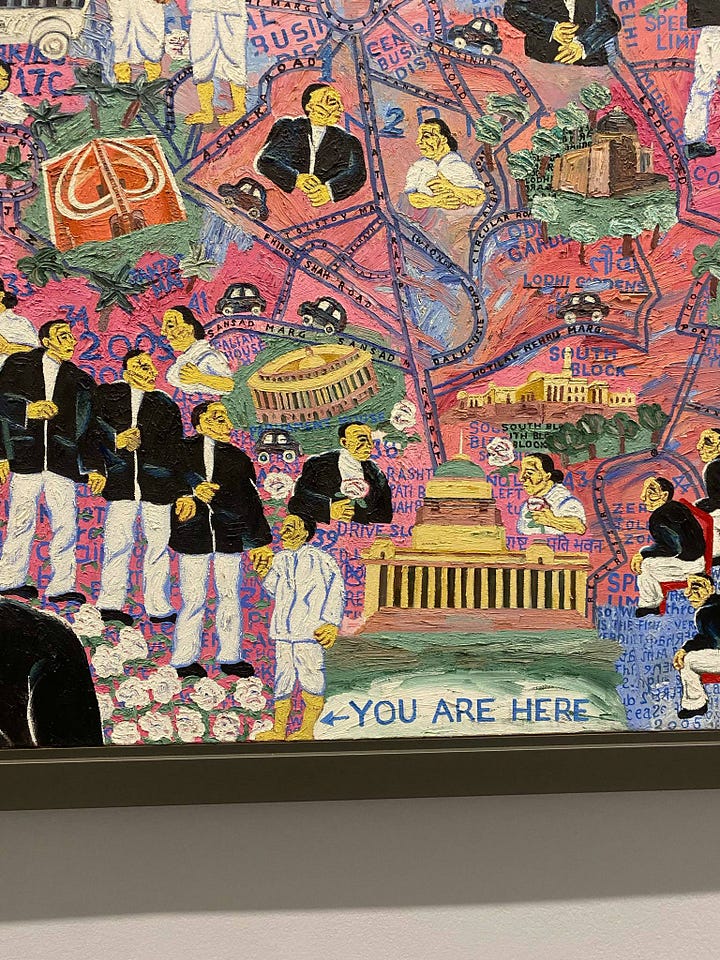

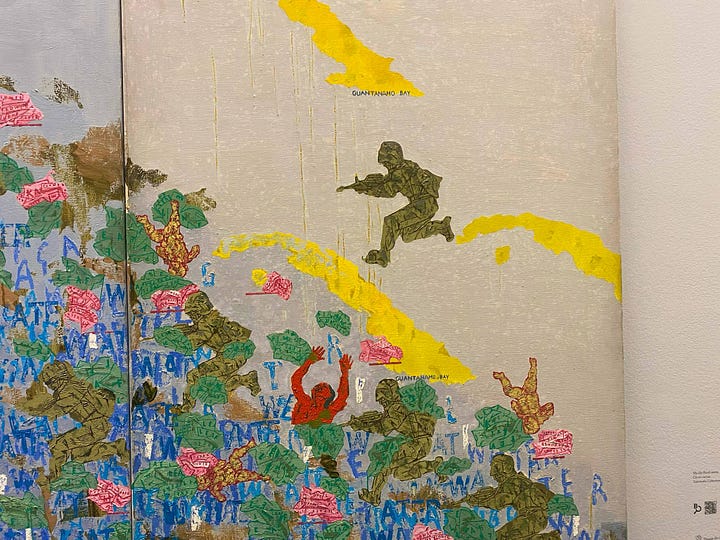

The thing that immediately pissed me off was the exhibit’s introductory note, which chose to highlight Singh’s background and her womanhood, noting that she often favours motifs like turtles, flowers, and mangoes in her work. Sure. But what I saw in the actual paintings were themes (and imagery) of guns, of class, of maps and their boundaries, of fucking Guantanamo Bay. It felt like an egregious oversight (if we’re being generous) of the gallery to present commentary on her work that fell so flat, and that (in my view) deliberately obfuscated its evident concerns with violence, militarism, borders, and political aggressions.

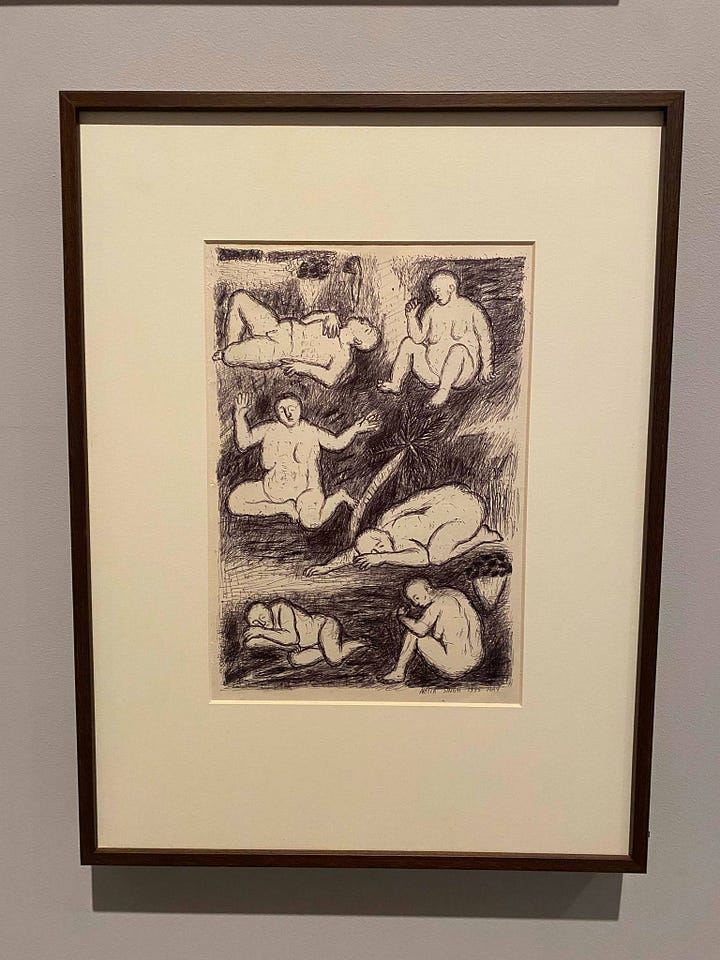

The art itself was extraordinary. I spent several minutes gaping at each object, genuinely afraid I’d miss something, lose the chance to be changed by it. Her works are full of texts, numbers, collage-like, chaotic systems of movement and objects that knot together with shocking seamlessness. I found her artistic vision so commanding, in that it left such little room for me to question any intentions, and to simply stare, awed.

On the way out, in a short documentary, she spoke Hindi, discussing her journey as a painter, talking about the trajectories of some specific works. She looked like my grandmother; the suit she had on (no dupatta) felt almost identical to one of hers. When asked about the typographic aspect of her work, she sheepishly admitted that she once accidentally painted something looking like an alphabet, and so just went with it, letting it become part of her oeuvre. She also said she’s never considered motherhood a major theme of her work, but that if you portray a small figure next to a big figure then it’ll naturally be interpreted as a baby –– an interpretation the gallery had in fact run with all over the exhibition. She spoke of her drawings, noting that they’re often described as ‘abstract’, saying that even though they don’t look like anything obvious, they taught her so much –– meine bohot kuch seekha.

Videodrome (Cronenberg, 1983)

I wrote about this here. I don’t directly address it in that essay, I think, so I will do so here. I am obsessed with how the film is basically Crimes of the Future but for TV instead of plastic, and TV to them is what phone is to us1, and what AI is, and what everything always is. Technology as a movable goal post is a timeless idea, but watching it captured so obsessively and grotesquely from the vantage point of right now felt incredibly transfixing. I become more of a Cronenberg fanatic each day, and my favourite thing about art currently is his signature gratuitousness, the freaky and grossness that I am so drawn to. Deeply enjoyable.

For your consideration:

Amber Husain, “A Disingenuous Prescription”, Too Little / Too Hard

I would find my life’s purpose as a kind of ethical necessity – the illness narrative as the creative product of a person who writes, not just to restore a hold on their life, but to furnish the lives of others.

the writer-as-worker can no more override the conditions of her entrapment than override the fact of being ill.

If someone or something outside you ensures that your hands are oversubscribed, ought you be named the exploiter, whose choices determine the rules of the game?

Donna Haraway, “Animal Sociology and a Natural Economy of the Body Politic: A Political Physiology of Dominance” — I’m currently reading her book Simians, Cyborgs, and Women and it is mind-numbingly good

These boundary creatures are, literally, monsters, a word that shares more than its root with the word, to demonstrate. Monsters signify. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women interrogates the multi-faceted biopolitical, biotechnological, and feminist theoretical stories of the situated knowledges by and about these promising and non-innocent monsters. The power-differentiated and highly contested modes of being of these monsters may be signs of possible worlds - and they are surely signs of worlds for which we are responsible.

More on Haraway:

Katie Gibson, “Bringing Abolition Home: Why Family Abolition Needs to be at the Heart of the Movement to Abolish Family Policing”, Blind Field

Protecting parents from criminalization is a valuable abolitionist aim. However, a political movement in which children are passively “tak[en] back” by adults who lay claim to them based on biological or legal ties reproduces rather than challenges the core logic of parent-child property relations that is upheld in a parental state.

A society where children can be psychiatrically hospitalized and medicated against their own wills but have no right to adequate mental health services is not a society designed in the “best interests” of children. It’s a society designed around the fantasy and tyranny of family.

Helena Aeberli, “phone noise”, twenty-first century demoniac — see note on Videodrome (above)

See Helena Aeberli, “phone noise”, twenty-first century demoniac